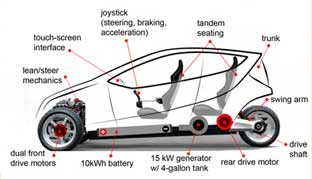

Sometimes an entrepreneur should reinvent the wheel, as Revolution Motors has done with its Dagne electric vehicle, which utilizes a joystick to steer and brake the vehicle. The key to the success of wheel reinvention is knowing when and where to implement such dramatic shifts from past precedent.

The car brake pedal originated with stagecoaches, which required the use of the driver’s leg muscle to stop the stage, due to the horses’ “horsepower” and the coach’s weight. Use of the driver’s foot also freed their hands to hold the reigns. The foot brake made sense on stagecoaches, but it is less than optimal on computer-controlled, modern vehicles*.

The car brake pedal originated with stagecoaches, which required the use of the driver’s leg muscle to stop the stage, due to the horses’ “horsepower” and the coach’s weight. Use of the driver’s foot also freed their hands to hold the reigns. The foot brake made sense on stagecoaches, but it is less than optimal on computer-controlled, modern vehicles*.

Like the brake, early cars’ steering mechanisms were drawn from legacy modes of transportation. Cars were initially steered via a tiller device, similar to that used to control a boat’s rudder. Ironically, such tillers were rudimentary approximations of a modern joystick.

Steering wheels were co-opted from sailing ships. One of the first uses of an automobile steering wheel was in Alfred Vacheron’s 1893 race car. After winning several high-profile races, Vacheron’s design became widely adopted. In 1898, C.S. Rolls introduced a commercial vehicle which incorporated wheeled steering and by the end of the following decade, tiller steering was a thing of the past.

Use of a steering wheel was logical, especially before the advent of power steering, as a large wheel required fewer revolutions to mechanically translate movement to the car’s front axle, whereas a tiller had a limited range of motion. However, the introduction of power-assisted steering eliminated the steering wheels inherent advantage.

Studies by DaimlerChrysler have shown that the reaction time between the hand and the foot varies significantly. The hand is approximately twice as responsive, due to the relatively small and nimble wrist muscles which react more quickly than the larger, less agile leg muscles. This difference in reaction rates is minute, but significant. A half-second of enhanced response decreases rear-end collision deaths by 90%, whereas the application of the brake a full second earlier reduces such deaths by 95%.

The major cause of front-end collision deaths is the combination of the driver’s compromised response rate and the subsequent impact of the steering wheel. Even with airbags and collapsible steering columns, the International Road Traffic and Accident Database notes that a significant percentage of the 50,000 drivers killed each year on US highways are crushed by the steering wheel. In fact, emergency responders are instructed to inspect the steering wheel at crash sites as a means of estimating the extent of the driver’s internal injuries.

If it is safer to eliminate the steering wheel and allow drivers to control the brakes with their hands, why do all mass-produced cars still utilize technologies which arose from stagecoaches and sailing ships?

If you haven't already subscribed yet, subscribe now for

free weekly Infochachkie articles!.

Familiarity might breed contempt in human relationships, but users’ familiarity with technology often breeds comfort that is difficult to overcome, unless the net benefits of the new solution are readily apparent and easily attainable. In addition, the legion of trial lawyers itching to dip their hands into the auto makers’ pockets also precludes dramatic design changes.

Letting Go Of The Status Quo

“The reason that God was able to create the world in seven days is that he didn’t have to worry about the installed base.”

–Enzo Torresi, Computer Industry Pioneer

Apocryphal stories which trace the size of the space shuttle’s gas tanks to the width of Roman roads make for entertaining reading. However, despite a multitude of Internet references to the contrary, there is no historical correlation between the ancient Roman standards and NASA’s Shuttle.

There is good reason that the Roman roads/NASA Shuttle story has been a fixture of business folklore for decades – it sounds plausible. Standards often remain in place beyond their useful lives, until a bold entrepreneur reinvents the wheel and devises a solution that is so much better than the existing one that existing users are willing to invest the time necessary to learn the new approach.

The Uninitiated

Adoption of wheel reinventions by Uninitiated Users, those who have not been previously exposed to legacy systems, is generally more rapid than by the general population, as such users do not have to “unlearn” an old way. In addition, their lack of affiliation with a legacy technology precludes them from feeling more comfortable with technologies of the past.

For instance, downloadable music and online players, such as Apple’s iPod, represent a reinvention of the wheel which was very easy for young, Uninitiated Users to adopt, as they had yet to establish strong music consumption behaviors. Older users, familiar with purchasing CDs, were generally slower to adopt online music.

Recumbent Incumbents

Entrepreneurs who free themselves from the constraints of standards can often create tremendous value for themselves and their users. Incumbent players have a far lesser incentive to accept the risks associated with inventing new wheels, as they perceive the status quo to be less risky in the near-term.

Incumbents must trade off delivering the minimum level of innovation demanded by their users and the degree to which they can maximize the return from their legacy know-how, processes and capital investments. Thus, recumbent incumbents, those which rest on their laurels, tend to be found in industries which have not experienced a recent wheel reinvention.

Auto manufacturers are classic recumbent incumbents. The major manufacturers in this mature industry have invested billions of dollars in developing better legacy vehicles. As they are rational investors, they prefer to maximize the value of these investments by profitably manufacturing as many internal combustion automobiles as possible. Although they are ideally positioned to lead the evolution to electric vehicles, their cars continue to rely upon their combustible engine expertise. This is particularly evident in hybrid cars, which utilize both electric and gasoline powered engines.

Incumbent players seldom have the worldview required to reinvent the wheel. For this reason, incumbents often make poor wheel-reinvention partners. Rather than struggling to change an incumbent’s worldview, entrepreneurs should partner with companies that have something to gain and nothing to lose by reinventing the wheel, even if such partners do not necessarily have extensive experience in the industry to be transformed. In the case of electric cars, producers of power storage devices make better partners than automotive companies, because wheel reinvention only represents upside to storage device manufacturers.

With no need to design backwardly compatible products, re-educate an established customer base, or abandon legacy processes and fixed-asset investments, a startup can focus on delivering its users optimal value, without slavishly paying homage to the status quo.

Users’ Return On Investment

An entrepreneur’s inherent flexibility to leverage the most productive and effective tools and methods is not a license to tweak conventional wisdom for the heck of it. Clearly most innovations do not warrant wheel reinvention. In order to determine which breakthroughs are worthy of such a momentous change, entrepreneurs should assess the following factors:

- Cost

- Performance

- Ease of use

- Change in behavior

Even if your new wheel is just as easy to master as the old one, adoption will be slowed and potentially thwarted based on the degree to which users must change their behavior. Thus, the greater the extent to which you can reinvent the wheel in a way that retains the users’ legacy behavior, the faster your solution will be adopted. One way to address this issue is to maintain familiar form factors, even if the underlying technology deviates significantly from the past. For instance, cell phones initially had a form factor similar to their landline brethren. Even Internet-based “smart” phones, which can do many things in addition to placing and taking calls, utilize the familiar 12-button keypad found on landline phones.

The combination of the new solution’s ease of use and the degree to which users must change their behavior represents the Learning Curve Investment required to derive benefit from the new solution.

Wheel reinvention is successful when the innovation delivers benefits that outweigh the combination of the Learning Curve Investment and incremental net costs or savings of the new solution. The User’s Return On Investment is derived as follows:

User’s ROI = Enhanced Performance - (Learning Curve Investment +/- Cost Differential)

As Kevin O’Connor points out in The Map Of Innovation, to be successful, any new solution must be significantly more beneficial and/or have a major impact on cost savings or productivity. According to Kevin, “A new solution has to be ten times as good or offer ten times the cost savings” of the legacy solution in order to motivate users to move from their comfort zone. This is true with any new product, but especially so when you are reinventing the wheel.

Quirky QWERTY

Urban legends aside, the QWERTY keyboard was not developed to slow down 19th century typists. In fact, research indicates that Christopher Sholes designed the QWERTY in order to minimize the clash of keys as they struck the paper, not to slow down typists. In addition, the QWERTY did not become the standard keyboard format overnight. It took a number of years, competing with alternative key alignments, before QWERTY became the standard. The design may not be ideal, but it has proven serviceable for over a century. However, the reason that QWERTY has remained the standard for so long differs from the forces that have kept the steering wheel and brakes in place.

Numerous studies have shown that various keyboard designs are slightly more effective than the QWERTY standard. However, the switching costs (i.e., the time and lost productivity associated with learning to use a new keyboard) that are required to become proficient on a better keyboard have outweighed the perceived benefits of switching. Typing slightly faster is not an adequate incentive to invest the required time to relearn basic keyboarding skills.

Another initiative that delivered a similar negligible User ROI was the United States government’s “go metric” campaign of the 1970s. After spending hundreds of millions of tax dollars cajoling, educating and ridiculing the public to “think” in metric terms, the U.S. government finally gave up, but not until long after it was apparent that the less-than-optimal legacy system of inches, pounds and ounces was “good enough” to deter most people from making the Learning Curve Investment required to master the metric system. One legacy of the government’s wasteful spending is National Metric Day, which is celebrated each October 10th by no one.

Location Cubed

Where you reinvent the wheel is of immense importance. For instance, if you attempt to introduce your new wheel in a market with powerful incumbents, they may aggressively marshal their resources to thwart your efforts. This has been the case in Europe with respect to genetically re-engineered food stocks. The entrenched agricultural chemical companies have subtly encouraged the “green” movement’s resistance to the introduction of genetically re-engineered foods.

When deciding where to reinvent the wheel, you should also seek markets with a high concentration of Uninitiated Users, as they will be less influenced by the incumbents’ attempts to prevent the entrance of your new wheel.

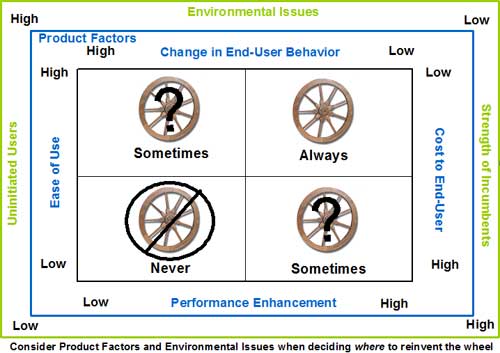

In addition to the four product-oriented factors, the following environmental issues must be considered when evaluating where to reinvent the wheel.

- Strength of incumbents

- Relative concentration of Uninitiated Users

The interaction of the four product factors and two environmental issues are shown below.

When And Where Should You Reinvent The Wheel?

The relative impacts of each of these product and environmental factors must be considered in concert. For instance, enhanced performance might be adequate to offset increased costs and/or low ease of use, especially in a market with few incumbents and a large concentration of Uninitiated Users. The key is to consider each characteristic on a continuum and in tandem with the others.

A new keyboard would fall in the upper left quadrant of the Product Factors box in the preceding diagram, which is indicative of a product that does not deliver enough value to justify the user’s Learning Curve Investment. Hence the QWERTY keyboard remains the standard. However, if you can locate a market that also corresponds with the upper left corner of the Environmental Issues box, you might successfully launch an improved keyboard.

Judgmental Dispassion

Before deciding to launch a product in a particular market, you must first assess its relative ease of use. This variable should be determined by a statistically relevant number of dispassionate users. You and members of your team are not appropriate judges of this attribute, as your passion for your adVenture’s solution will make it difficult for you to accurately assess the User’s ROI.

Objectivity is also paramount in your assessment of the product factors. For instance, most Mac users believe it is relatively “easy” to convert from a PC to a Mac, whereas the typical PC user views such a conversion as more challenging. As this instance illustrates, Uninitiated Users, who were not forced to forego a legacy solution, are generally not the best judges of an Initiated User’s ROI.

Inertia Is Not Inert

Inertia is a standard’s best friend. Educating and encouraging users to adopt new solutions can be time-consuming and expensive. This certainly was the case at Computer Motion, where we not only created new products, but simultaneously pioneered the medical robotics industry. Before we could discuss our products’ benefits, we were forced to have long conversations regarding the efficacy of introducing robots in the operating room.

The Learning Curve Investment for surgeons was tremendous. However, as the Users’ ROI was overwhelming (shorter patient hospital stays, lower overall costs, fewer risks of complications, etc.), surgeons eventually either retired or made the investment to learn the new robotic methodology.

Don’t Trust Anyone Over 30

Entrepreneurs should not trust any standard or method that is over 30 months old, let alone 30 years old. By consistently challenging old-world conventions, entrepreneurs can identify wheels whose reinvention is not only worthwhile, but immensely lucrative. Even if a wheel is not wholly replaced, the simple act of exploring alternatives can lead to valuable innovations. Thus, leverage the fact that no customers, no sales and no legacy investments provide you with the freedom to deploy the ideal solution, not one that largely relies on the legacy approach that has gone before you.

As Harold Evans points out in the conclusion of his insightful and comprehensive review of entrepreneurship entitled, They Made America, “Time and again in this study we find that breakthroughs come from the discarding of assumptions. Ignorance that ignites curiosity is a better starting point than half-knowledge.”

As Harold Evans points out in the conclusion of his insightful and comprehensive review of entrepreneurship entitled, They Made America, “Time and again in this study we find that breakthroughs come from the discarding of assumptions. Ignorance that ignites curiosity is a better starting point than half-knowledge.”

A startup’s ignorance of the status quo can be a powerful ally when it attempts to devise a new solution to an old problem. Who knows? You may just come up with a revolutionary new wheel, just like Revolution Motors.

Note: Some of the examples cited in this article were drawn from an inspiring talk given by Mr. Calestous Juma, Ph.D., Professor of the Practice of International Development at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.

—

Copyright © 2008 by J. Meredith Publishing. All rights reserved.

*Andonian, Rauch & Bhise, Driving Steering Performance Using Joystick vs. Steering Wheel Controls, SAE Technical Paper Series, 2003.

Pingback: Knowtu » links for 2008-11-27

Pingback: Leverage Your Startup’s Origin Story To Reinforce Your Mission & Values

Pingback: Steering wheel · Expand Wisdom